Heriberto Ruiz Tafoya

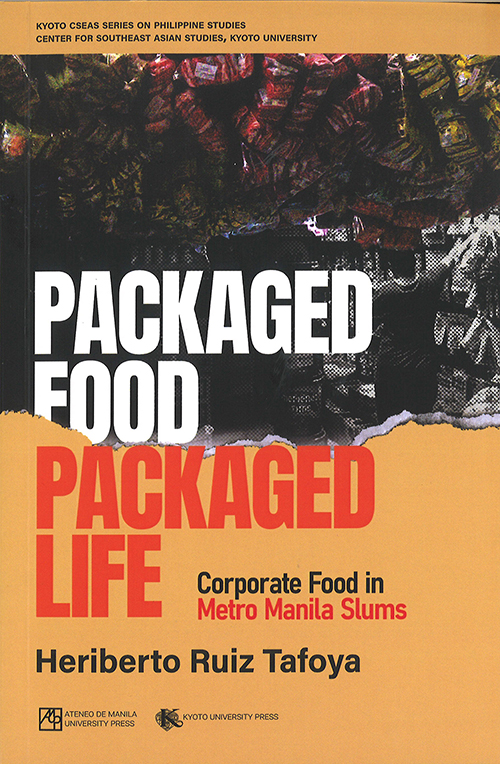

Packaged Food, Packaged Life: Corporate Food in Metro Manila Slums

Kyoto University Press & Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2023

https://www.kyoto-up.or.jp/books/9784814004751.html?lang=en

1. Could you summarize the essence of this book in a few words?

The book elucidates why Corporate Packaged Food is ubiquitous in all market spaces of Metro Manila’s slums, finding that it is not simply because poor people can afford it or that the phenomenon is due to individual lifestyle choices.[1]The book clarifies that the abundant consumption of corporate brands in slums is the result of historical circumstances in which constrained living conditions and limited opportunities for people to flourish as human beings facilitate the supply of these commodities to the poor.

I am among those scholars who reject such packaged food, because corporations market their brands in search of profit and without caring about the food quality or the impact on nature, people, and culture. The technology of packaging food to protect it from humid weather, insects, and animals is perfectly acceptable, but the problem is that such technology is mostly in the hands of corporations. In the book, I suggest that this type of packaged food should be used at the minimum and that people should have access to packaging techniques and technologies to preserve their own food, freeing them from having to rely on the food that the corporations provide.

At the entrance of a sari-sari store in the slum of Dakota, Malate, Manila that I regularly visit to chat and interview family members.

[1]Corporate Packaged Food (CPF) includes packaged, canned, and bottled foods, beverages, condiments, and fats. Unlike (ultra) processed food, manufactured food, junk food, and convenience food, CPF is distinct in its prominent placement of a corporate brand on the packaging.

2. Could you tell us about the events or ideas that led to the writing of this book?

It was my first visit to Metro Manila in late 2013. That year, the Pan American Health Organization and the World Health Organization declared that Mexico, my country, was a nation with an epidemic of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension.[2]This was prompted by a series of health and nutrition surveys conducted since 2000, which had found high levels of these diseases for the first time in so-called “developing countries” (the declaration also included Brazil). The common conception and media representation of a Mexican had been of a slim but strong man or woman with tanned skin who is physically strong enough for sports and for arduous work in agricultural fields, factories, and construction sites. But, in those early years of the 2010s, we became more conscious about how fat, weak, and sick our bodies were getting. Gerardo Otero (2017) called this the result of the “NAFTA Neoliberal Diet.” We imported food and consumption habits from North America, where the larger bodies of white and Anglo-Saxon people were also obese. Most of the diet consisted of sugary, fatty, and salty processed and ultra-processed foods. In later years, I came to call these Corporate Packaged Food for reasons related to the following.

In 2013, I was an MBA student in Japan. At the time, it was fashionable in business schools to discuss the idea of profiting from the poor, who textbooks and case studies called the “Bottom or Base of the Pyramid (BoP).” This expression was popularized through articles in the Harvard Business Review and the 2004 book by C.K. Parahalad entitled The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, Eradicating Poverty through Profits. The World Bank, the IMF, the Asian Development Bank, and many government agencies and big corporations promoted the idea of harnessing the market potential of the four billion consumers in the world whose per capita incomes were, at the time, less than US$ 1 per day. The BoP business idea is to offer this population “meaningful,” affordable, and adaptable products and services that they are willing to pay for. Food and beverage manufacturers such as Nestlé, Danone, Ajinomoto, Unilever, and Kraft were already adapting their business model in line with this idea to retail affordable food and beverages to the poor.

With this information in mind, upon arriving in Manila, I was struck by the sheer number of single-use packaged food and beverage products (tingi-tingi) being sold everywhere—from neighborhood stalls and shops (sari-sari) to modern retail outlets like convenience stores, pharmacies, and supermarkets. A simple and quick observation of the consumption dynamics of the city immediately reminded me both of the health crisis happening in my country and the entrepreneurial education we received as MBAs. That education promoted providing more of these products to the “excluded” poor people (or, in other words, those previously uncaptured by the market) to “include” them in the benefits of the commodity-based economy.

Corporate branded packaged foods for sale in a Badjau community settlement at the periphery of Metro Manila. The wall of packaged foods provides a splash of color in the slum.

Children outside a sari-sari store.

A customer at a sari-sari store interacts with the grocer inside (unseen in the photo). We can understand the friendly and relax way in which they interact daily.

My goal became not only to understand this phenomenon, but also to construct a critique of it.

[2]See the Report of the 6th Meeting of the Pan American Health Organization in 2013 at: CSP28/R13 – Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases – PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization and https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/51523/9789275320327_spa.pdf

3. Could you tell us about any difficulties or challenges you faced during the writing process and in getting the book published?

I faced many difficulties doing fieldwork in the Philippines because I am not Filipino, my language is Spanish, and I lived in Japan. The Philippine urban context is very complex culturally, linguistically, religiously, socially, politically, economically, historically, and so on. It is one of the most complex places I have ever been in my life. It is even more complex than Japan, which is itself a difficult society to understand.

Inside the Nonoy Sari-Sari store on a day when I stayed in the stall from 8 am to 8 pm to take note of a typical Sunday activity in the Meralco squatter area. This was a key part of observing the social reality of the slum from inside the store.

In front of a Nonoy sari-sari store in the slum of Meralco; to my right is the owner, next to her is my hostess in this slum. To my left is a younger sister who helped me in my fieldwork. It was through her social network and trust that I was able to meet the people in Meralco. She also regularly translated for me what people were saying.

With some elders of the Muslim community in the Dakota slum in Manila. From these wise men I learned much that changed my appreciation of food, society, politics, and life itself.

Another difficulty was finding a way to enter the slums safely, and above all, finding a way to gain trust while being with the people in these neighborhoods. I was fortunate to receive help from NGOs and religious organizations that assisted me in any circumstance, especially at the beginning of my contact with various peoples described in the book.

In the university, I (like any other masters and doctoral student) also faced difficulties because most of the theoretical advances—supposedly done to frame our understanding of the world—were realized in Europe or North America. Thus, we must learn to argue with concepts, frameworks, and theories from those countries to explain complex realities such as those in the slums of Metro Manila. I spent about nine years of my life at this task until the completion of the book. Unlike my doctoral dissertation, in the book I have used a framework that comes from indigenous peoples’ traditions in the Philippines and Latin America. For this reason, it is best to compare my book with my doctoral dissertation, because while the dissertation includes more theoretical discussions of political economy, the book takes a more anthropological and sociological approach and thus includes more voices.

4. Could you give some tips and hints to young researchers on how to compile various facts and analyses into a single work when writing a book?

I think it is better for everyone to find their own way, rather than to follow others, since every research topic, every circumstance, and every person is different. However, it is useful to cross-reference what people in the community or neighborhoods say or do, what literature on the topic says, what professors and colleagues say, and most importantly, the researcher’s original point of view while in the field.

Talking about my book with a local man.

Sharing about my book with people in Metro Manila.

5. Please tell us about any new research topics you discovered while writing this book that you would like to explore further, and also about your plans for your next book.

I discovered and would like to learn more about non-urban indigenous communities in the Philippines. In the city, I would like to learn more about the women of the carinderías (eateries). I interviewed eight such women and lived with one, Tita Amparo, whom I deeply respect. I have in mind to write a book about these women and other cooks in a family daily-life context. If I had political and economic power, I would support carinderías (financially and politically) to preserve their cultural and social value.

In the house where Tita Amparo used to live. The food was cooked and sold on the day of the photo in her carindería business.

With Tita Amparo in her carindería business on a street next to the Barangay Government office of Payatas.